To discuss whats happening in the Muslim world and what can we do about it.

Wednesday, 30 March 2022

Monday, 28 March 2022

Friday, 25 March 2022

Thursday, 24 March 2022

Wednesday, 23 March 2022

Tuesday, 22 March 2022

How Anti-Muslim Propaganda Is Spilling into India’s Film Industry

The Bollywood produced film The Kashmir Files opened in cinemas throughout India and the rest of the world on Friday. It tells a story about the exodus of Hindus – the Pandits – from Indian administered Kashmir during the early 1990s.

The script could have easily been written and directed by Hindu nationalist paramilitary organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) or its political wing – Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Kashmiri Muslims are portrayed as bloodthirsty killers and rapists, while Kashmiri Hindus are cast as hapless and defenceless pacifists, who refuse to take up arms against so-called “jihadists”, a pejorative term used to cloak local opposition to Indian rule in Islamic extremism. Expectedly, the Indian Government’s eternal bogeyman – Pakistan – lurks sinisterly in the background.

In a climatic point in the film, the late Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto screams: “We will never allow Kashmir to become an integral part of India,” among calls for jihad from local religious leaders, therefore echoing the current Indian Government and its supporters, who have long accused Kashmiri Muslims of being puppets of Pakistan.

Kashmiri Hindu women and children are shown to be shot mercilessly in the head from point blank range, as radicalised Muslims roam the streets of Srinagar in search of their next victim. Historical facts be damned. This is the telling of a Pandit “genocide”, according to the film’s producers, who blend Hindu nationalist tropes with garden variety Islamophobia and straight up falsehoods.

For starters, there’s virtually no evidence that a Hindu genocide occurred in Kashmir during the 1990s.

Even the Indian Government reported that fewer than 220 Pandits were killed in Kashmir during the period spanning 1989 to 2004, a number that was contradicted by Srinagar district police headquarters in 2021, when it reported 89 Pandits had been killed during the past 31 years.

If this meets the definition of genocide, then so does the killing of 1,800 Muslims in Assam in 1983, the mass murder of 2,000 Muslims during the violence that swept Gujarat in 2002, and the Delhi Riots in 2020, which left 51 Muslims hacked, burned, and shot to death. But none of these mass atrocities were called a genocide, a term that has been reserved by Hindu nationalists crimes committed by “Islamic extremism”.

More to the point – if 89 to 219 dead Kashmiri Hindus equates to genocide, then what name do you give to the killing of at least 50,000 but potentially 100,000 Kashmiri Muslims by Indian occupation forces since 1989? And what name do you give to their nearly 10,000 unmarked graves?

Were you to count the number of inconvenient truths omitted from the screenplay, you’d not only run out of fingers and toes, but also marbles and loose change. The producers do not want the audience to know that the exodus of Pandits took place under Jammu & Kashmir Governor Jagmohan Malhotra, who was appointed by the central Government, which was supported by BJP.

For this reason, Kashmiri Muslims insist that the exodus was a “concentrated effort” by Jagmohan Malhotra to first “clear the Pandits from the valley, before turning the guns on their vulnerable selves,” writes Vijaylakshmi Nadar in a recent op-ed for the Indian Observer.

In mythologising the tumultuous political events that swept the valley during the early 1990s, The Kashmir Files not only advances Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda by further polarising the electorate, but also legitimises the persecution of innocent Kashmiri Muslims at the hands of Indian occupation soldiers.

It’s impossible to ignore that the movie is being released two years after the Government stripped Kashmir of its semi-autonomous status, while imposing draconian lockdowns, curfews, mass arrests and communication blackouts. And at the same time BJP leaders vow to make Muslims second-class citizens, while some Hindu nationalist leaders call for a Muslim genocide.

Worryingly, the movie is being screened for free in many Indian cities, which will only whip up further hatred towards Muslims and drive a great number of Hindus towards BJP’s ultra-nationalist agenda, one that posits Islam and Pakistan to be a threat to the country’s Hindu majority.

To this end, The Kashmir Files accords with the imagination of the Indian Government’s unofficial Ministry of Propaganda, with Islam, Muslims, and Pakistan making a fearsome presence in every scene.

In India, we have a ruling party that not only draws its ideological inspiration from the Nazi Party, but also serves up propaganda to promote Hindu nationalism, the political ambitions of BJP, while demonising political opponents and Muslims.

Indeed, the Indian Government has helped pay for the film to be promoted in the United States. It knows that if it can get American audiences to see Hindus as victims of radical Islamic terrorists, then it can silence US opposition to its Hindu settler-colonial enterprise in Kashmir.

Modi has carefully studied how pro-Israel groups have undermined political support for the Palestinians in falsely framing Palestinian resistance to Israeli occupation as the product of Islamic extremism, not secular resistance to colonial rule.

The Kashmir Files does exactly that to Kashmir’s Muslim majority population.

Monday, 21 March 2022

Friday, 18 March 2022

Thursday, 17 March 2022

Abandonment of newborn girl child a sign of Pakistan's repressive mentality

Pakistan is plagued with its frenzied obsession for a male heir and in the process scores of girl babies are abandoned in the country which speaks volumes of Pakistan's repressive mentality. The recent incident in the Mianwali district of Punjab province in Pakistan unveiled the unfortunate state of affairs of a girl child in the country.

A seven-day-old infant was gunned down by her father named Shahzeb because his first child was a daughter instead of a son. The cruel father shot his baby five times, reported ARY News. The news has been circulating on social media. Users have shared pictures of the infant that can be seen dead. The government in Pakistan is also notorious for skipping such heart-wrenching instances.

Pakistan's societal preference is nothing new as the newborn girls in Pakistan often go missing. Scores of infants are left in white metal Edhi cradles and the more unfortunate ones either get tossed in the nearby trash dumps or are conveniently buried elsewhere, reported The Daily Times. The requirement for the time is to apprehend the culprits and put them behind bars. These deplorable incidents might make headlines however this is not enough as action needs to be taken against those who transpire such horrific crimes.

According to the last year's 'Global Gender Gap Report 2021', Pakistan ranked 153 out of 156 countries on the gender parity index, that is, among the last four. It ranked seventh among eight countries in South Asia, only better than Afghanistan. Pakistan's gender gap has even widened by 0.7 per cent points in 2021 compared to 2020.Notably, since the Imran Khan government came to power in August 2018, Pakistan's Global Gender Gap Index has worsened over time. In 2017, Pakistan ranked 143, slipping to 148 in 2018.The report indicates that Pakistan needs 136 years to close the gender gap, with its existing performance rate. These statistics show that overall progress in reducing the gender gap is stagnant in Pakistan in four areas: economic participation and opportunity; educational attainment; health and survival, and political empowerment.

Wednesday, 16 March 2022

Tuesday, 15 March 2022

Murdered women: Adiba Parveen, the quietest girl in the valley

“People in the village would say Adiba was an example for us,” Sajina says. “They would refer to her when they would scold us, reminding us, ‘She is so shareef, so quiet and polite, she does not gossip or waste her time with idle chatter.’” When her friends were old enough to whisper about boys, she found it amusing. “Why would you waste time on them?” she asked.

When friends and family members talk about Adiba, there is a common refrain: she was a good girl, a well-behaved, responsible, polite girl. But she loved to sing – even when she did not know the lyrics, even when she deliberately changed them to make people laugh – and the only times this good, well-behaved girl seemed to do exactly as she pleased was when she was singing.

“She had this habit of standing outside her house and singing very loudly,” recalls Sajina. She knew her neighbours laughed at her. Sometimes, Sajina would join in. The girls would stand outside and sing at each other, scrambling lyrics and singing through their giggles, their voices spilling over into their neighbours’ homes. “Tu hai pagal, tu hai joker (you’re crazy, you’re a joker),” Adiba would shout to Sajina, a lyric from one of her favourite songs, from the Bollywood film Raja Hindustani.

There was another game the girls loved to play. Like most of the homes here, they did not get running water, and every day women walked to the Shimshal river to fetch water. When it was time to head there, one of the girls would stand outside her home and whistle a tune. “That’s how we would summon each other,” Sajina says. The neighbours learned their code: the sweet, clear signal followed by the girls’ chattering voices as they traipsed off.

The river is a five- or six-minute walk from Sajina and Adiba’s homes.

“That’s where they found her on that day,” Sajina says.

They found her by the riverbank, her legs in the water. She would have been washed away were she not pressed against some stones. For a moment, Bakhti Baig believed his sister lay there sleeping.

A crowd quickly gathered and whispered amongst themselves. It was all too common, they knew, for young men and women in the region to commit suicide. While they had not dealt with this in Shimshal, it was so prevalent in Ghizer, Gojal, Chitral, Baltistan or Gilgit, that in 2017 a government committee had been formed to investigate. There were a range of contributing factors: unemployment, mental health issues, domestic abuse, despair at the lack of economic opportunities. The villagers knew that in most instances, families did not bother to report the deaths and quietly buried the victim.

It took the police a few hours to arrive from Hunza. Bakhti Baig was bewildered, unsure of what to do next. The police told him the body needed to be taken to Gulmit, three hours’ drive away. Someone would have to stay with the body overnight until samples for a post-mortem could be collected in the morning and sent to Lahore for processing. There are no facilities to conduct a post-mortem in Gilgit-Baltistan.

By the time the samples collected at Adiba’s post-mortem made their way to Lahore, they were entirely unusable. There was no conclusive report on the cause of her death.

“Adiba was not the kind of person who would kill herself,” Rahat explains. “We want the tasalee, the gratification, of knowing this for sure.” The brothers filed a First Information Report (FIR) with the police, accusing Adiba’s father-in-law Sameem Shah, mother-in-law, husband, brother-in-law Fahim and sister-in-law of killing her and attempting to dispose of her body in the river. The suspects were arrested, but by mid-June, all except Sameem and Fahim were set free. On August 9, they were also released on bail. The accused all denied responsibility for Adiba’s death.

Adiba’s family refused to stay quiet. “I received a message from one of her brothers asking me to write about the case,” says Noor Muhammed, founder and editor of Pamir Times, an online news service covering Gilgit-Baltistan. Muhammed’s wife, Amina Bibi, is one of the administrators on a strictly private Facebook group for women from the region. She decided to reach out to the members and they organised protests against the Shahs’ release.

In August, people gathered in Shimshal, Gulmit, Islamabad and Karachi to call out, “Justice for Adiba”. “When I saw the number of women at the protest in Gulmit – young and old, their children with them – I began to weep,” Amina says. “I have grown up seeing women with bruises, blackened eyes, making excuses for how they got the injuries, being told, ‘Bardasht karo’ (you must bear it). But that day, the women didn’t want to be silent any more.”

Noor Muhammed says he was “pleasantly surprised” by the protests and the determination of Adiba’s family to get her story out. “We are a tribal culture – we live in close-knit communities and when you take a stand against someone in your community, you risk being cast out,” he explains. “This generation is no longer taking the vow of silence our elders did for the sake of the family or tribe’s honour and respect.”

By the end of August, the Shahs’ bail was cancelled. The victory has come at a cost for Adiba’s family. “I have spent Rs500,000 so far on legal fees and the expense of travelling for every hearing,” says Bakhti Baig. “We sold whatever we could. I am so tired, I don’t know how to go on.”

They persist as it is the only way they can make amends to Adiba. “I wish I could tell her, ‘This will not happen to another of our girls’,” Rahat says. “We want this case to be a lesson for people in Shimshal.”

Mehrunissa’s children saw the protests for their aunt Adiba. They do not understand what happened to her, but in the days after, they played a new game: they would march through the house mimicking the calls they had heard, chanting, “Justice for Auntie Adiba!” The case did not receive much media coverage outside Gilgit-Baltistan. “But at the protests, even strangers had Adiba’s name on their lips,” says Mehrunissa. “If it weren’t for them, who would know about her? Adiba was an ordinary girl. She died. That’s it. Why would they care?”

Monday, 14 March 2022

Saturday, 12 March 2022

Wednesday, 9 March 2022

Monday, 7 March 2022

Friday, 4 March 2022

Wednesday, 2 March 2022

To achieve peace is not easy........

Whilst I was in Abu Dhabi for an International peace conference organised by Shaykh Abdallah Bin Bayyah and Shaykh Hamza Yusuf, I met this Hindu religious leader from India. He told me that once during Ramadan he had slept in his local Mosque in order to reach out and show solidarity with the Muslim community against a rise in Islamophobia attacks, where Muslims had been attacked and Mosques vandalised. He told me that months later his temple was burnt down by extremists claiming to be Hindu, because he had displayed a public act of support for the Muslim community.

I asked him, despite receiving death threats and intimidation, what kept him strong and focused, knowing that he has a family to look after. His reply was:

"To achieve peace is not easy, and you have to make immense personal sacrifices. I will continue to support Muslims. If we sincerely care for people, and want to our communities thrive in respect of each other, then we have to be courageous by firefighting evil with goodness. This is the only way to defeat spiritual ugliness."

From FB page of Nadeem Ashfaq

Tuesday, 1 March 2022

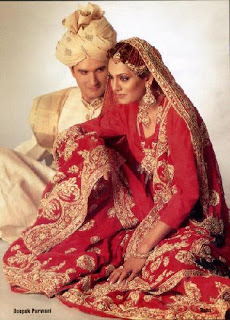

Marriage in Pakistan is a marry one get one free deal — marry your husband and get his entire family too

“You are being removed from your family, and moved into this one, your husband's,” said the Nadra officer. I saw him drag and very literally drop my name from one document to the other. “Now you’re part of their family.” I felt my eyes tear up a little and tried to catch my breath. My husband later joked about how the Nadra officer had gotten me more sentimental than the nikahkhwan.

This incident led me to mentally prepare myself a year ahead of my ruksati — any chance I got I spoke to friends, friends of friends and family members about their experiences after getting married, especially women who found themselves in joint family systems. A year later I found myself sometimes struggling but mostly naturally manoeuvring and settling into a new life and family. These conversations made me grateful in some situations and in others helped me take a step back. But all of the stories stayed with me.

For example, a newly-married 27-year-old told me she wasn’t allowed to have cheese in her new home. As bizarre as it may sound, it was true — her father-in-law received a WhatsApp forward about processed cheese being cancerous, “So now we can’t have cheese, I literally have to destroy the evidence if we have a cheese omelet”. I think she saw the disbelief on my face, because she added, “I’m serious, I would rather that my father-in-law finding me smoking up than eating cheese”. We all laughed and when I asked her how she dealt with it, her reply really stuck with me — “It’s his house”.

Why does no one talk about moving in with people you’ve met just a few times in your life? What does it mean to “adjust” into a new house and a new family?

According to an article in The Washington Post, the University of Kentucky’s Department of Communication conducted two studies on depression in newly-married women. In a study of 28 women conducted in 2016, nearly half of the participants indicated they felt depressed or let down after their wedding. They also reported clinical levels of depression. Another study conducted in 2018 of 152 women showed 12 per cent feeling depressed after their wedding.

For most South Asian women the post-marriage depression strikes a few weeks or months later. Maheen*, 30, recalled, “Once you’re back from the honeymoon and the dinners end and life starts to normalise, you find yourself in someone else’s house and you’re thinking 'okay, when do I go home', but this is home, but at the same time it’s really not”.

For 29-year-old Hina*, it was made very clear that this wasn't her house. “I come from a very conservative community where girls are married off very young. I was 21 and I remember my mother-in-law told me on the very first day that this wasn’t my house,” she said. When I asked Hina how she was made to feel this way, Hina laughed and said, “Oh, she very literally told me that this isn’t my house and that this is their house and their rules were meant to be followed".

Hina’s experience is unfortunately not rare — moving out of your home for a woman in Pakistan doesn’t necessarily mean starting anew with your spouse. It often means you have to “adjust” into a family where your diet, spending habits and general lifestyles is altered. There's also an unspoken rule — don’t change the environment, change yourself. The sign of a “good” daughter-in-law is when she takes up less space, doesn’t speak her mind and is subservient not just to her husband but everyone in his family as well.

Twenty-nine-year-old dentist Sidra* recalled that she and her husband got into a fight when she refused to serve his brother breakfast. "Religiously I’m not supposed to but my husband told me religion aside, this is our culture. It just didn’t seem fair. I work as well and have to reach the clinic before my husband and I never complained about doing his work but I drew the line at serving his brother. The argument kept growing to a point where I went back to my mother's the next day,” she said.

Sidra’s situation may seem extreme but culture in our country often overrules religion. “I am supposed to look after not just my husband but his parents as well, and it just makes me mad because had my mother been in the place of my mother-in-law she would actually help me instead expecting me to clean up after her,” Samra* who got married last year told me over the phone. “It’s a sham when they tell you your mother-in-law Is like your mother. She really isn't.”

When I asked my friend Amina* about the one piece of advice she would give a new bride, she had a very simple reply. “Be yourself — this is something I was not. I was the best version of myself, but that didn’t last very long. I was exhausted after a while, which disappointed my in-laws. Just be who you are and don’t give them a chance to complain about how you’ve changed after getting married.”

Women from South Asian cultures have newly come to terms and accepted the idea of normalising and de-stigmatising depression, postpartum depression as well as emotional and physical trauma. My personal discomfort of accepting I was depressed in this perfectly sound new environment made me feel ungrateful because of which I invalidated and dismissed my short and sometimes long bouts of depression.

“There is resentment you feel towards your husband for the way he smoothly settles into his life where nothing for him changes. But for me everything changed, and he didn’t even acknowledge it,” Beena* told me about her experience moving cities. “Do men realise how lucky they are? They can open the door to their mothers’ room, I have to wait for the holidays and book a ticket.”

What I learnt is that no one is going to prepare you, no words or stories can save you from the vehement misplacement you feel when you’re living with a family familiar and harmonised with each other’s patterns and even habits that may be unpleasant to live with. Listening to these stories made me feel like I hit the jackpot with my in-laws. So why was it that I felt this strange sadness that over took me randomly? Often, I silenced that feeling because of the horrors stories I had been listening to for almost a year. It was not until much later that I realised the advice I wished to have received from married women instead of table setting, in-law dealing and money managing was that randomly crying on random afternoons was normal, seeing your husband sitting next to his mother watching TV and feeling resentment that I couldn’t do the same was natural and feeling lost during a big dinner with all your in-laws was going to get better.

I wish someone had told me this was all going to happen and I didn’t have to deny myself the grief or sorrow. That that period of bereavement wasn’t permanent, that my feelings were valid. But most of all, that I wasn’t being ungrateful nor did it mean I loved my new life or my husband any less, but there were things that this new home didn't have — my mother’s voice waking up, my father handing me a plate of cut fruit or that heart-to-heart conversation I had with my sisters before falling asleep or references to the many inside jokes I have with my brother. In this culture which we cling on to so dearly we don’t talk about the agony women leave with when they separate from their families, the stress during the move and the separation anxiety that follows.

How do I explain to the men in my life the feeling I endure when I am standing outside the door of the room that was once mine at my parents' house? Where I see pieces of my life and have to decide what to take with me and what to leave behind? What do I do with the despair I feel and the frustration that comes with it? Instead, we tell these women they’re not the first to part with their families. Instead we call them a bridezilla, difficult or moody. Moving in with another family is like a migration you make, it will always involve loss. Sometimes it hits you sooner and sometimes its inside a Nadra office.